My reliable source of Cambodian food paranoia, the Lonely Planet Cambodia (4th Ed.) opens their paragraph on Cambodian food with the

…colonial adage that says ‘if you can cook it, boil it or peel it, you can eat it…otherwise forget it’

Following with bleak warnings against ice, shellfish, salad, steamed foods, empty restaurants and vendors wallowing in their own insalubrity. I don’t ascribe to the maxim that you should look at whether the vendor looks healthy because maybe he’s had a rough night on the Mekong whisky and I’d hate to deny him a round of his favourite tipple after an oily day behind his deep-fryer. Short of the vendor suffering something that can be recognised as transmissible via food, I’ll give them my time of day and fistful of riel. Originally I set myself the rule that I’d never knowingly eat in a village where somebody had recently died from diarrhoea but after consulting some World Health Organisation statistics on childhood diarrhoea mortality I realised that in most of rural and urban Cambodia, I would be going hungry a good deal of the time.

I tend to eat more food from the street in Cambodia than your average tourist as well as eating everything that the LP warns me against and tend not to ever injure myself doing so. I don’t have a cast-iron stomach and accordingly, I eat in a way that I consider sensible. Here’s my rough guide to surviving street food.

1. Heat : Hot food should be served hot. Your pho should steam. Your deep-fried banana should burn the tips from your fingers through the inadequate newspaper wrapping. If it doesn’t look like it might lift the skin off the roof of your mouth, don’t order it. Avoid foods from the streetside bain maries in Cambodia: generally you can get exactly the same dish cooked for you fresh in most small Khmer restaurants for less than a dollar more with better produce and surroundings to boot.

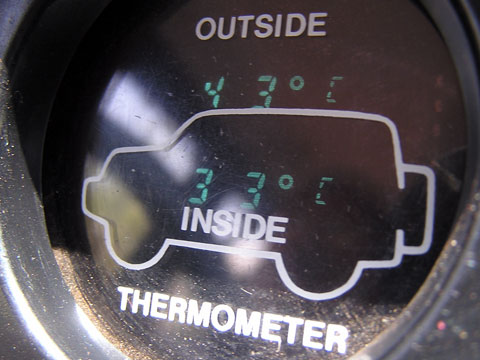

2. Cold : Cold is an entirely different matter. Ice tends to be a problem where the water has been contaminated prior to being frozen or the ice has been contaminated in storage or transit. If you’re having a bad day, both. Cambodia’s drinking ice supply is excellent: the only people that I’ve met who have been sick from the ‘ice’ has been when it was combined liberally with a dozen beers. The only cold food that I avoid on the streets is the ice cream as vendors commonly unfreeze then refreeze their wares, coupled with the ice cream itself not being tasty.

3. Timing : In Phnom Penh, people stick to rigid schedules. Many are up at dawn and thus breakfast starts roughly after sunrise and continues no later than 8:30am. Breakfast foods, especially the ubiquitous pork and rice, are best consumed early. For most office and factory workers, lunch begins at exactly 12:00pm and runs until 2pm. Hitting a roadside lunch spot after 1pm often will mean that you’ll get the dregs of the soup and the fried fish that the rest of the locals rejected. With the exception of mixed fruit smoothie (tuk alok) and the occasional fried noodle vendor, there aren’t many late night street food options yet.

4. Other patrons – This is important for two reasons. Firstly, if people are spilling over onto the pavement and into the street, it’s an accurate indicator that the food is either tasty or underpriced. Even if the food is dirt-cheap, if people are pulling up to a stand in both Landcruisers and Honda Chalys, it gives a good indication that the food crosses economic boundaries and that it is worth people stepping down from their high (or in the case of Chalys, low) horse to dine amongst the plebs. Secondly, it’s a great indicator of how quickly the food turns over. Busy venues tend to be constantly cooking or at least refreshing their food as quickly as possible and thus you’re likely to receive fresher produce.

5. Family tag team – if the more than one member of the same family works at the stall, this is always an excellent indicator of a top notch venue. It means that their stall is lucrative enough to support the entire cohort. Be on the lookout for husband and wife teams, and award bonus points if they have kids in school uniforms (outside of school hours), because they’ll be the ones starting the next Jollibee.

6. Don’t eat stupid things : A good guide to judging the stupidity of a food is that if the locals believe primarily that a food will give you strength or vitality in the pants department rather than chiefly eating it because it tastes appealing. Some foods stay as provincial delicacies for one of three reasons: they’re either shit, endangered or they kill you. If snake’s blood was really that delicious, McDonald’s would have a cobra-flavoured sundae. I’m all for eating new and random (but not endangered) things but remember to keep your expectations very low and your bowels at maximum readiness, because when you do discover something that is loosely edible, it will taste like the food of the gods.

Continue reading 6 rules of Cambodian street food eating